Shooting Crows

- Caroline Clarke

- Oct 2, 2024

- 2 min read

Updated: Mar 21, 2025

Shooting photo reference of crows, that is.

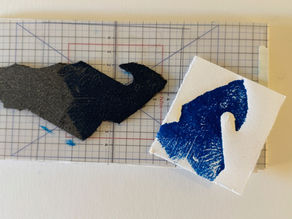

I want as little friction as possible when I sit down to work on my crow studies. With a stack of reference photos ready, I'm drawing in seconds. The same goes for media exploration sessions. Using a single reference photo, I make multiple pictures with different media and compare the results. Going for a playful crow? How'd that turn out with brayer and paint? With soft pastels and charcoal? This use of reference materials is straightforward, and I use it daily.

Good photo reference is critical for crow studies. Anatomy — how wings attach to the body or how many toes a crow has. (Four. Three in the front, one in the back, as it turns out.) What makes the crow so recognizable? Photo reference captures characteristic silhouettes, behaviors, and poses — their turn of the head, their sauntering walk, and fingered wings in flight. A couple of drawings from photo reference go a long way in warming up my hand, eye, and purpose.

From where?

A quick Google image search turns up photo references that are terrific for media exploration and crow studies. Websites with just-the-facts images, like National Geographic and Cornel Lab's Birds of the World, are good sources. Professional and amateur photographers also post online—my favorite of these is Joel Sartore's Photo Ark.

Then, there is UnSplash, with over 29,000 pictures of crows and Flickr, with close to 400,000.

When I shoot my own reference, it's rarely as pretty as these. My photos are often from a distance and turn out grainy, with a wing or tail cropped inconveniently. But these, too, inspire.

Here's how it works —

I'm on a walk, and a crow catches my eye. I snap a photo. As much as I'd like to try different angles — I mostly just manage to point, shoot, and hope.

My backyard is full of crows this time of year — the fruit trees are bearing gifts. They watch first from the apex of the roof, then alight together on the pear and apple trees below. If I get too close, they take off, skimming my fence, and are gone. So, lately, I've been taking videos.

Back in the studio, I look at what I've got and select the most interesting ones — maybe for the point of view, the activity, or the lighting. I review the videos and freeze some promising frames. These go into the Viz Ref app on the iPad and, just like that, become reference material for studies and media exploration.

A smattering

Afterword: Sometimes, my human viewpoint bothers me. All my shots of crows are taken from above (looking down at the crow on the ground) or from below, aiming my camera at telephone wires and rooftops. The crows are wary when they're on the ground and don't let me get close. While a telephoto helps, I've yet to manage a prolonged photo session. And in the air . . . fantasies aside, I can't fly alongside them. How, then, to get some idea of these other perspectives? And, while I'm at it, various lighting scenarios?

I'm trying out artificial intelligence (Dall-e) to create my reference materials. I'll write about that on another occasion.

—————

I, too, have studied crows, and indeed ravens, for years now. There are several ways to distinguish the American Crow (Corvus brachyrhynchos) from the Northern Raven (Corvus corax). They both have the same number of pinion feathers but when in flight, crows have five “finger” feathers that are prominent while the raven have 4 very long finger feathers. So, as they say, the difference between the two is a matter of a pinion...